Cable management has long ceased to be a matter of “aesthetics” or neatness. Cable management has a direct impact on operational safety, fault tolerance, infrastructure flexibility, and the cost of building maintenance, from office spaces to industrial and energy facilities. Mistakes made during the cabling phase are almost impossible to fix without downtime, noise, dust, and major infrastructure interventions.

Despite the development of wireless technologies, wired data and power transmission systems continue to be actively used. This is due to the requirements for the physical level of security, stability of data transmission and reliability of power supply. In many facilities, data transmission and power supply remain exclusively wired, which means that the cable infrastructure becomes a critical part of the building.

The Main Methods of Laying and Their Limitations

There are several common approaches to cable management: laying in concrete, through floors, in the ceiling space, and also under the floor. Each method has its pros and cons, but the key evaluation criterion is not the cost of installation but the convenience of operation, access to cables and the possibility of reconfiguration.

Concrete laying and shingling create a rigid infrastructure. Any change – adding, transferring, or replacing cables—requires cutting concrete, additional engineering calculations, and stopping work. In multi-storey buildings, this is complicated by the need to intervene on several levels at once. Such decisions often lead to increased project time and increased operating costs.

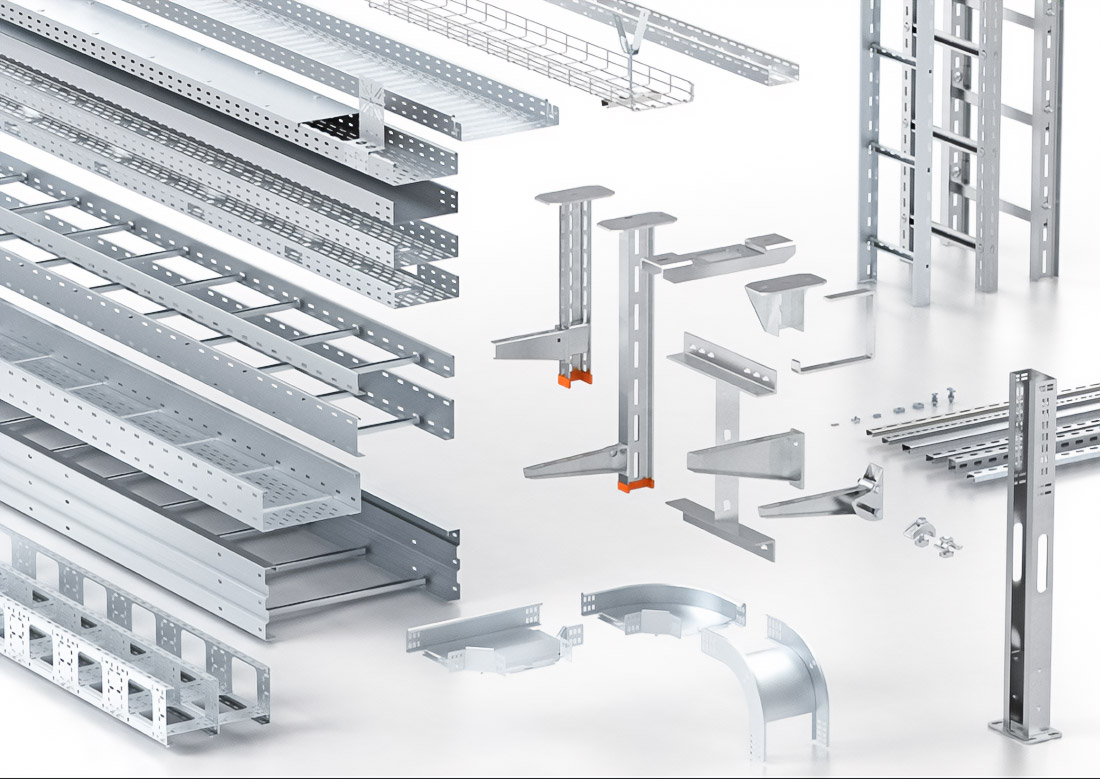

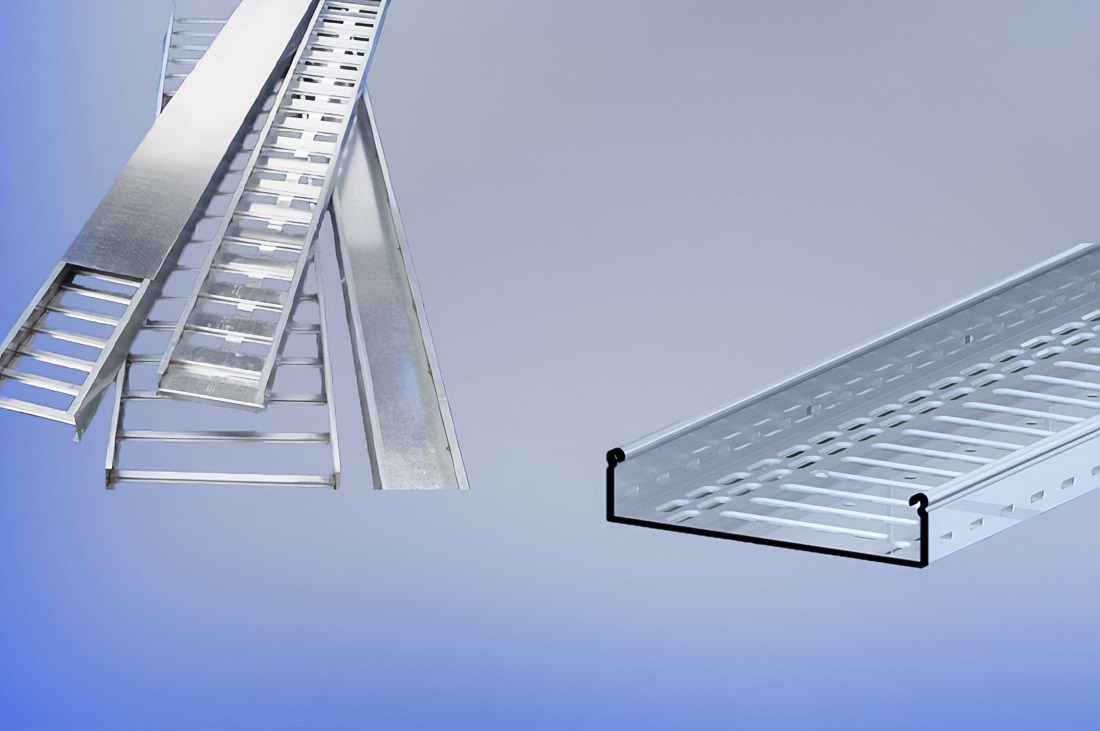

The ceiling gasket and overhead tracks provide more flexibility but pose other challenges. Maintenance requires ladders, repetitive movements of specialists, and constant work in uncomfortable conditions. In addition, cable descents into the workspace degrade the visual order and complicate the organisation of workplaces. In such systems, the role of a cable ladder supplier becomes critical, as load capacity, spacing, and long-term durability directly affect safety and maintenance effort.

Underground cable management solves some of these problems through hidden wiring, but accessibility remains a key factor. If access to the cables is difficult or requires intervention in neighbouring rooms, any reconfiguration becomes a source of downtime and inconvenience.

Flexibility and Lifecycle of the System

The infrastructure of a building rarely remains the same. Jobs are changing, equipment is being added, and the workload is increasing. The cable system must be designed not only for the current configuration but also for scaling.

Practice shows that up to 61% of facilities face problems with cable management during operation. However, more than 80% of these problems are directly related to wiring, and about 26% of system failures are caused by damaged cables. This is a consequence of overloading the routes, incorrect routing, lack of gaps and unaccounted for mechanical load.

Cable management, which focuses only on installation rather than maintenance, inevitably leads to increased repair time, increased labour costs, and reduced fault tolerance.

Safety, Wear and Technical Risks

Improper organisation of cables increases several risks at once: mechanical wear, overheating, electromagnetic interference, and damage to connectors. When stacked tightly without gaps, the cables rub against each other, which accelerates the destruction of the shells. This is especially critical when differences in cable diameters and materials are identified.

Engineering practice shows that electrical cables require at least about 10% of the free space of the diameter, and for more loaded lines – up to 20%. Ignoring these values leads to heat accumulation and an increased probability of failures.

A separate problem remains the lack of tension relief. When the cable is “hanging” on the connector, it is the port that takes on the mechanical load. This is one of the most common causes of equipment damage, especially in workplaces with movable elements and adjustable furniture. Correct use of cable tray and accessories plays a key role in controlling routing geometry, spacing, and strain relief across the system.

Workplace Organisation and Visual Order

At the workplace level, cable management directly affects ergonomics and productivity. Cable chaos most often occurs not because of the number of devices, but because of the uncontrolled behaviour of cables: long routes, intersection of power and data paths, accumulation of adapters and excess length on the floor.

Practice shows that visual clutter is usually formed at three points: on the front edge of the table, in the form of a “waterfall” of cables behind the countertop and in the floor area. Solving these problems does not require the purchase of additional accessories but thoughtful routing: allocation of separate paths for power, data transmission and peripherals, as well as a clear definition of the cable exit point.

It is especially important to consider height-adjustable workplaces. If the system is not designed for movement, the cables are stretched in extreme positions, which leads to damage and failures.

Long-Term Efficiency and Operation

Short-term savings on cable management almost always result in higher costs in the future. Mass replacements, downtime, increased maintenance requirements and reduced reliability are a direct consequence of decisions made without taking into account the life cycle of the system.

Durability-orientated systems provide access to cables, the ability to quickly reconfigure, wear protection, and reduced reliance on highly skilled manual labour. This is especially important against the background of a shortage of specialists and the increasing complexity of the infrastructure.

Cable management is not a secondary element but the basis for the stable operation of the building. The safety, flexibility, operating costs and service life of the entire infrastructure depend on how well the cable routes are organised. Solutions that take routing, access, gaps, load, and future changes into account can avoid most problems even at the design stage and keep the system manageable throughout its lifetime.

“The only impossible journey is the one you never begin.” –Tony Robbins